The Transoceanic Fliers Conference of 1932

From May 22 to May 30, 1932, a remarkable gathering occurred in Rome. The Italian Aero Club held a conference for transoceanic aviators to discuss the implementation of commercial air links between the Americas and Europe. Mussolini’s air minister, Marshal Italo Balbo, led the congress of aviators. The conference hinged on the appropriate routes for transoceanic flights, the infrastructure to support them, and most contentiously, the rights of international access to key air terminals. The most notable feature of the event was the remarkable assemblage of many of the most distinguished aviators of the time.

Fifty-three “fliers” attended, though the American contingent was fairly small. Charles Lindbergh could not attend because of the immediate aftermath of the kidnapping and murder of his son. Amelia Earhart successfully arrived in Ireland near the start of the conference as the first woman to fly the Atlantic solo, but elected to recuperate rather than attend. None of the crewmembers of the NC-4 that, in 1919, made the first aerial transoceanic crossing were there either. The minimal American contingent was led by Holden C. Richardson, whose principal transoceanic claim was reaching the Azores in the NC-3 after nearly being lost at sea as part of the Navy’s 1919 transatlantic flight. Richardson lacked the authority and stature to significantly influence the proceedings. He was assisted by Lt. Cmdr. P.V.H. Weems, the navigational expert, who also happened to be the only non-flier invited to the conference. Harold Gatty, a Weems associate and chief navigation engineer for the Army Air Corps also participated and was the strongest American voice ( despite not being an American citizen).

The conference was notable for its attempt to reach international agreements on the establishment of rules and protocols for international air travel. Unfortunately, questions of national privilege and the subsequent tensions with the fascist states meant that the conference ultimately yielded little in terms of actual agreements. Only with the post-World War II reshuffling of power and the increasing respect for international bodies were these questions finally settled with the rise of the United Nations and the International Civil Aviation Organization.

The conference faced its greatest struggles over whether airports were like seaports that (at least in times of peace) were to be open to vessels of all nations. France had already obtained exclusive landing rights in the Azores that would allow them potentially to dominate transatlantic service on northern routes. The Italians vehemently opposed this arrangement as Mussolini and Balbo saw Italian successes in long-distance aviation as key to increasing Italy’s global prestige and power and desperately wanted their traditional colonial rivals to be restrained in this field.

The conference did encourage international cooperation on establishing a common transoceanic infrastructure for commercial air service, including weather forecasting, wireless radio stations, and other facilities. However, those companies (like Pan American Airways or Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei) that succeeded in sustaining transoceanic service in the 1930s did so by developing their own systems of infrastructure.

Weems documented some of the contentious international struggles of the questions of international air routes and how access to airspace was to be controlled in contrast to maritime tradition. The National Air and Space Museum has acquired many of Weems’ papers, including his notes and mementos from the conference.

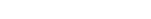

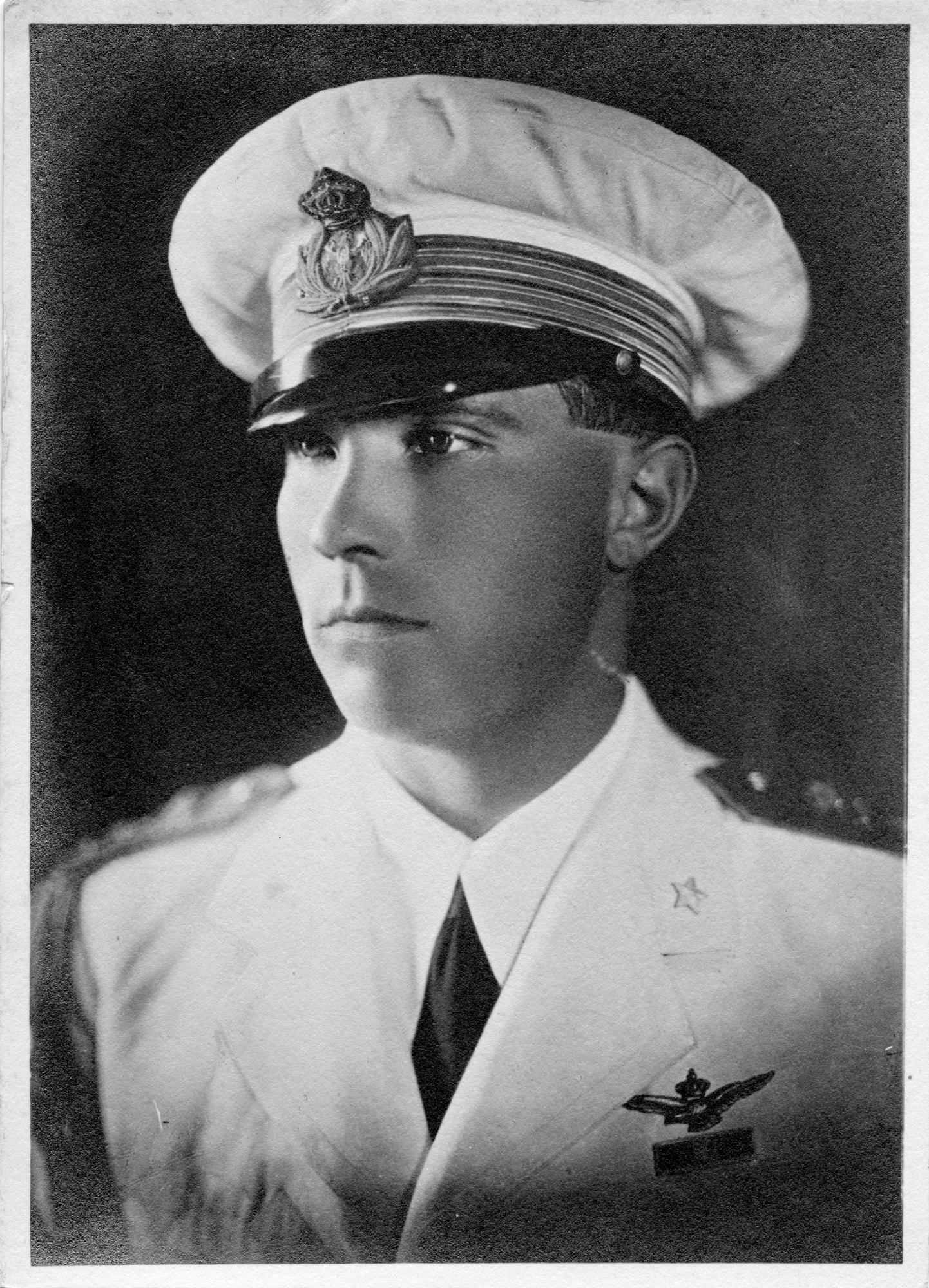

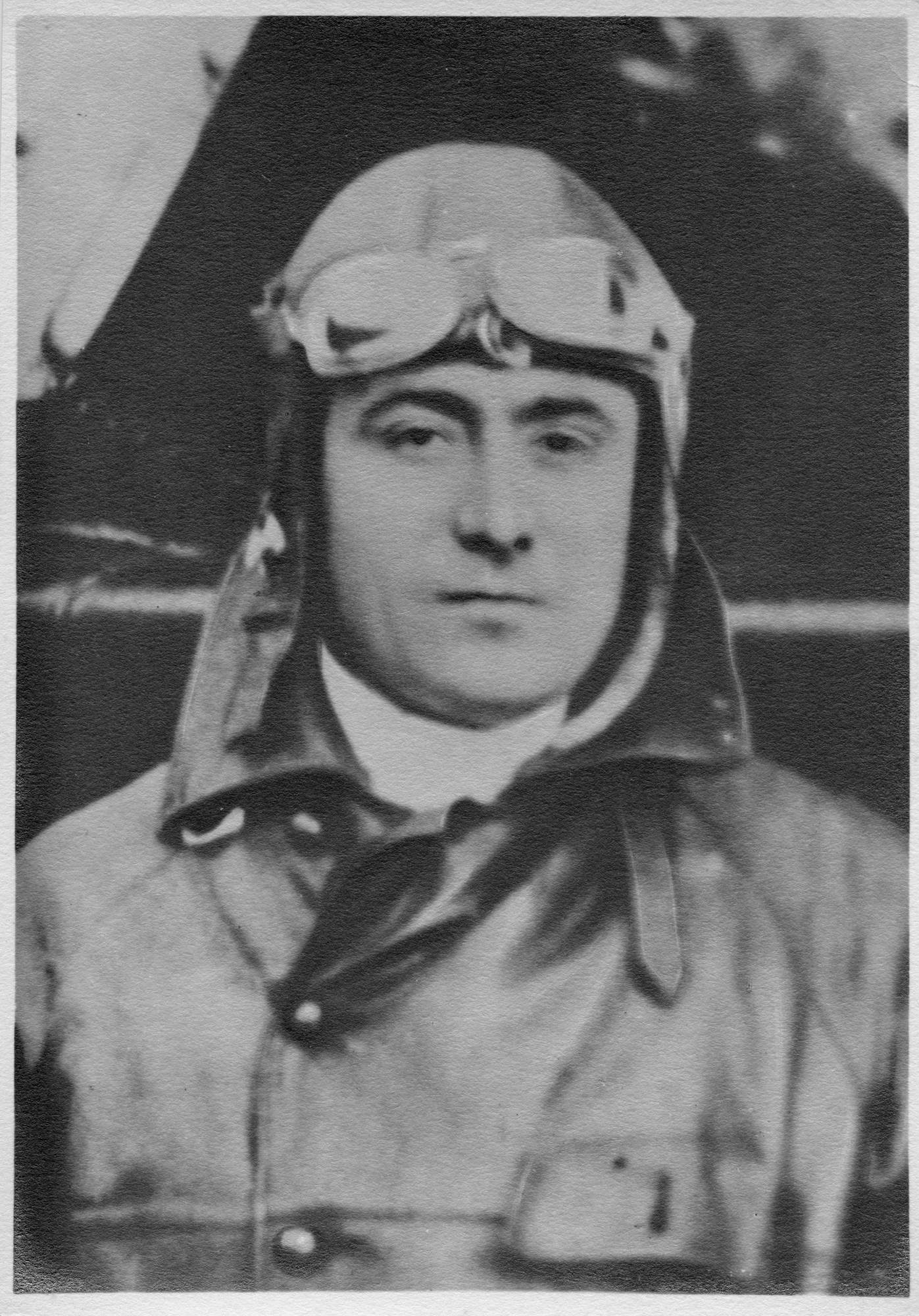

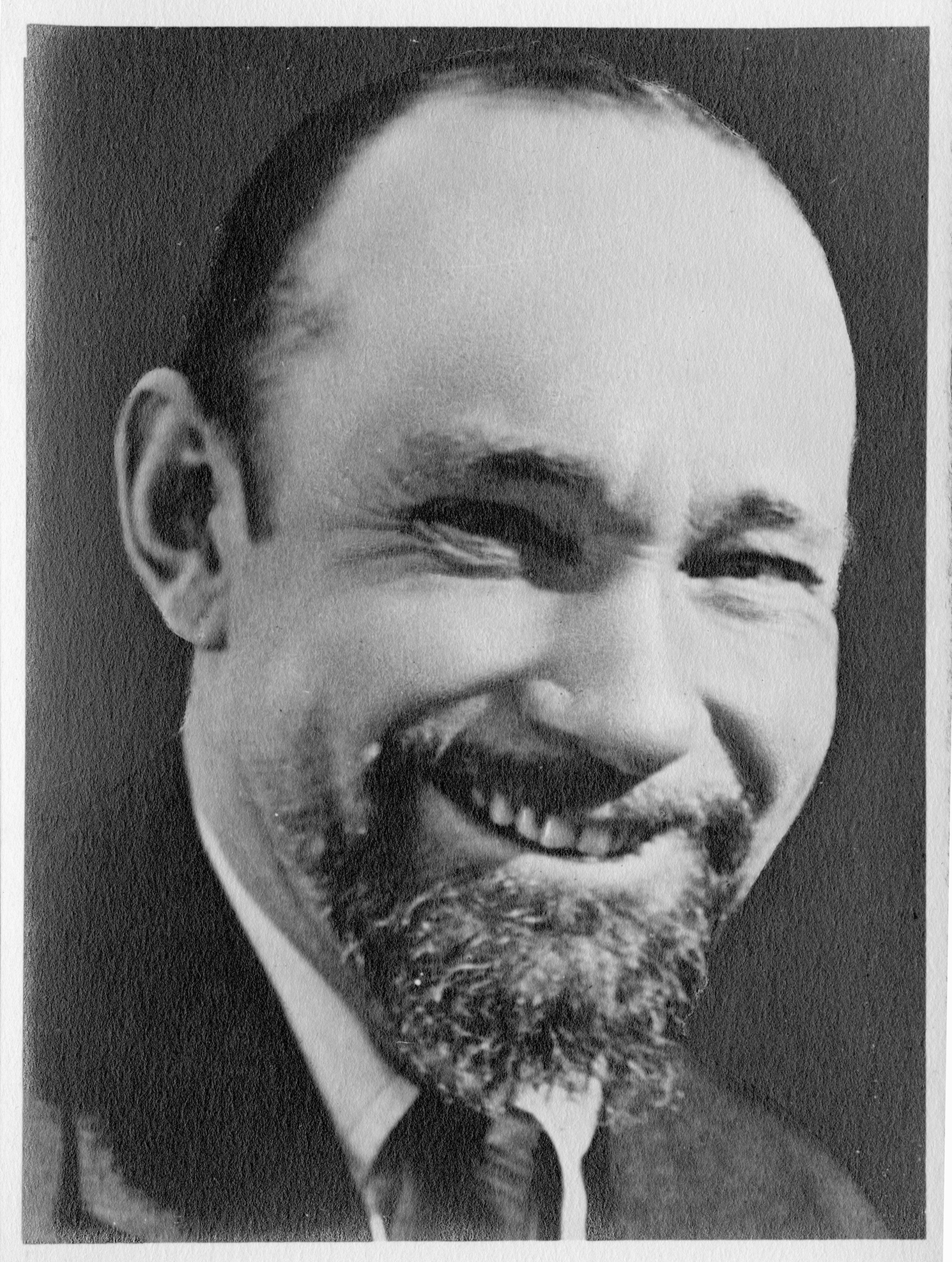

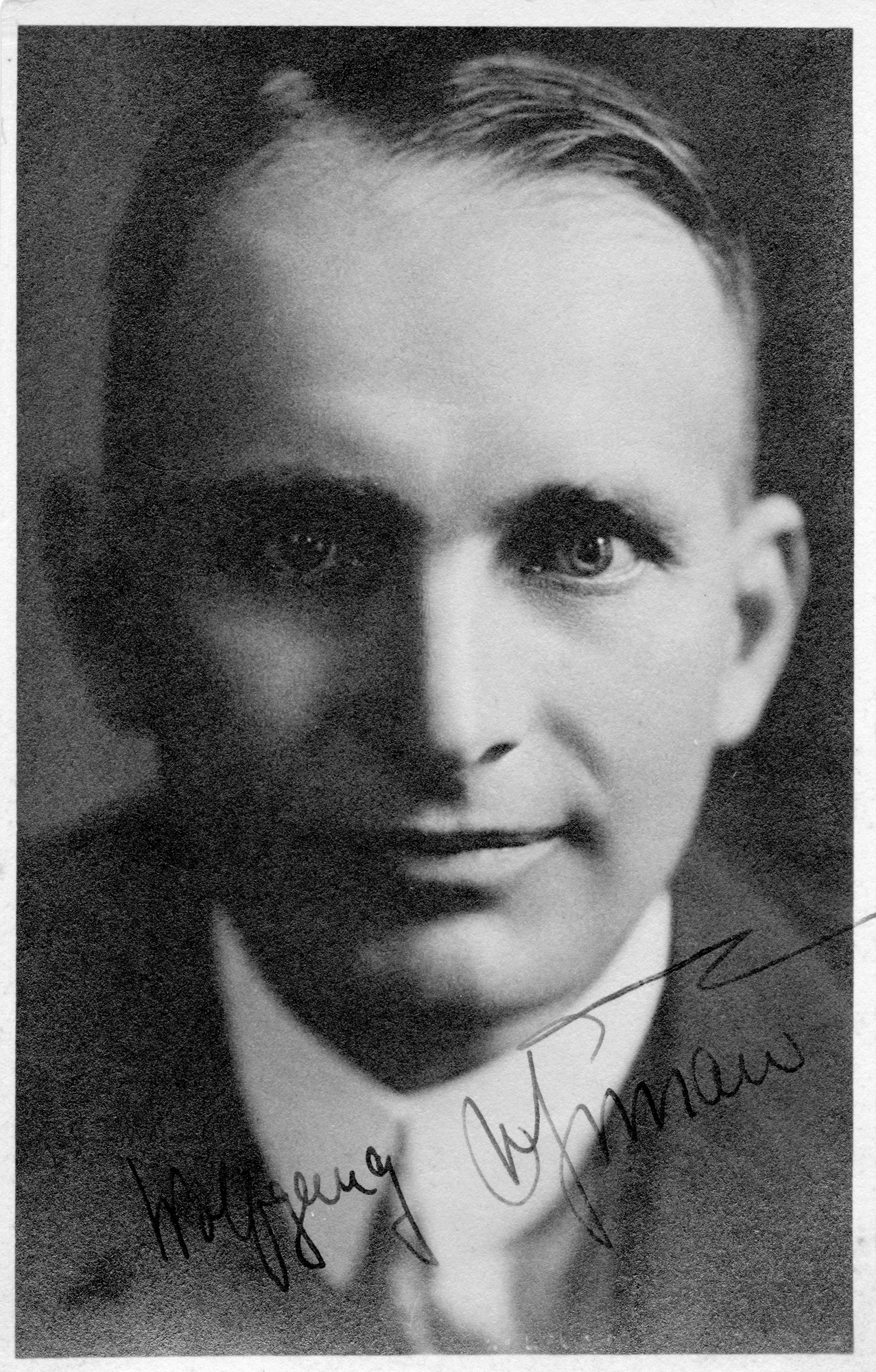

In the first grouping of items from the conference to be catalogued here, there is an extensive array of portrait cards that depict most of the attendees. Not surprisingly, they focus heavily on the Italian hosts – most notably Balbo’s famed “Atlantic Squadron” that flew from Italy to Brazil in 1930-1931 (and after the conference, to the 1933 A Century of Progress World Exposition in Chicago.)