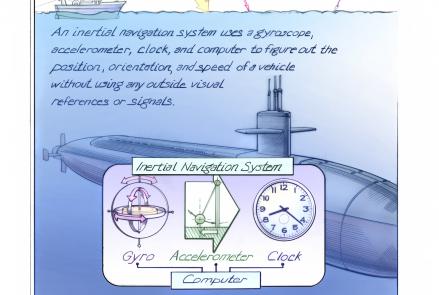

Though inertial navigation emerged nearly simultaneously out of several different programs in the United States and Great Britain, the person most associated with the creation of practical inertial navigation is Charles Stark Draper.

In 1945, while working at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, he began developing an automatic bombing system for the U.S. Army Air Forces that ultimately resulted in advances in measuring acceleration with precise accelerometers in combination with reference gyroscopes. By 1953, a large and cumbersome system called SPIRE (SPace Inertial Reference Equipment) was ready for testing in a transcontinental flight on board a modified B-29 bomber. The flight proved the effectiveness of the system, and Draper worked through the mid-1950s to create practical systems for the U.S. military. In 1954, Draper’s MIT Instrumentation Laboratory had partnered with the Sperry Corporation to create a prototype SINS (Ships Inertial Navigation System). In 1958, the first nuclear-powered submarine USS Nautilus used a competing SINS system to make its famous voyage under the North Pole. By 1960, inertial navigation had become a critical core technology for all U.S. military submarines, strategic bombers, and ballistic missiles.

As inertial navigation systems have decreased in size, complexity, and cost over the subsequent decades, their use has spread widely beyond the strategic military objectives of the Cold War. Inertial navigation has been especially critical in space navigation, but even the basic smartphone of today often features capabilities that only several decades ago weighed hundreds of pounds and cost millions of dollars.