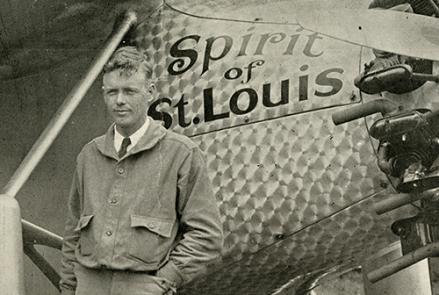

Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 transatlantic flight highlighted the limitations of early air navigation technology.

Though not the first person to cross the Atlantic by air (over 100 had preceded him), Lindbergh demonstrated that transatlantic flight would soon be practical. Because he lacked any means for fixing position, his flight also illustrated that, until better navigational tools and techniques were developed, this type of flying could be a gamble. Indeed, many who attempted it perished.

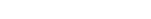

Lindbergh's Simple Tools for a Difficult Crossing

Lindbergh navigated the Spirit of St. Louis on his transatlantic flight with an earth inductor compass, a drift sight, a speed timer (a stopwatch for the drift sight), and an eight-day clock.

Despite weather deviations and extreme fatigue, Lindbergh reached the coast of Ireland within 5 kilometers (3 miles) of his intended great circle course. But he knew that chance, not skill or equipment, had allowed such accuracy—winds during his flight had caused no significant drift.

Besides being uncertain of his position at times on his transatlantic flight, Charles Lindbergh found himself lost several times on his Caribbean and Latin American tour. In each case, faulty equipment let him down. He realized he had to find better ways of fixing position if he was going to continue to make long-range flights and promote safe long-distance air travel.