With LORAN, navigators went from using mechanical-based time measured in seconds to using radio frequency-based time measured in microseconds (millionths of a second).

Mechanical clocks and watches that referenced a standardized time became less important to navigation, because electronic systems such as LORAN could accurately calculate a relative position with their own internal time.

This achievement was only possible through massive national investments in developing and combining the technologies of radio transmission and timing.

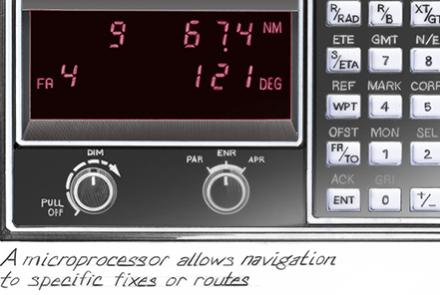

LORAN’s heart was its timing unit—a crystal oscillator that allowed a receiver on an aircraft, ship, or submarine to measure the difference between “master” and “slave” radio pulses. Early LORAN equipment was sensitive, and operators had to monitor it carefully, especially in areas with salt air and high humidity, which rapidly corroded components.

Many LORAN stations were in remote, inhospitable places. They required extensive infrastructure—personnel quarters, water and fuel tanks, communications equipment, and electrical generators—such as the one in Adak, Alaska. Duty here was dull and tedious, but also relatively safe compared with many types of wartime service.

By the end of World War II, LORAN chains consisting of 72 operable stations provided navigation over 30 percent of the globe, mostly in the northern hemisphere. More than 70,000 receivers for aircraft, ships, and submarines had been built. By the height of the Cold War, coverage had extended to 70 percent of the Earth’s surface. The ionosphere and terrain limited daytime coverage, so LORAN was far more effective at night.